From All Ends of the Earth

LONDON, JULY 26, 1911 — Ho hum, another conference comes to another conference hall. Probably be the usual stuffed shirts, cigars and brandy and blah blah blah. But wait! The delegates are arriving!

Here come the Turks in their scarlet fezzes. Next a smattering of sikhs with turbans tightly wound. The American delegation, in suits and ties, includes several “Negroes,” a Sioux, and a surprising number of women. Then there are Japanese and Koreans, Slavs from Russia and Hungary. Africans in bright skullcaps called “kufis. . .”

“The problem of the twentieth century,” wrote one delegate to this First Universal Races Congress, “is the problem of the color line.” And in 1911, the problem was usually labeled “The White Man’s Burden” to uplift “your new-caught sullen peoples, half devil and half child.” Yet for three sweltering summer days, in the heart of London, the only “problem of the color line” was finding a seat.

Nearly 2,500 delegates came from 50 countries. The assembly included professors, politicians, religious seekers, mystics, and more, all dreamers of a better world. The audience included novelist H.G. Wells, social worker Jane Addams, and a young lawyer from India named Gandhi. There were Muslims and Christians, Hindus and Baha’i. . . There were Buddists and Baptists, atheists and agnostics. . . Every shade of skin color was proudly displayed. Every method of greeting, from handshakes to ritual dance, was celebrated. It must have been wonderful.

Because in 1911, throughout the rest of the world, “the color line” was no mere “problem.” In America, five dozen blacks were lynched. All of Africa remained carved up by colonial powers, not just the British from Egypt to South Africa but the French in North Africa, the Germans farther South, the Portuguese in Angola. Southeast Asia was also bastion of white power. The entire globe, thoroughly yoked under the White Man’s Burden, had just 78 countries, compared with more than 200 today. But for three days, in one hall, near London Bridge. . .

Opening the Congress, a speaker from India called on delegates to “discuss, in the light of science and modern conscience, the general relations subsisting between the peoples of the West and those of the East, between the so-called ‘white’ and the so-called ‘colored’ peoples.”

An hour later, the Congress heard a hymn composed by W.E.B. DuBois. Stepping before the sea of faces, the prim, mustachioed DuBois began:

O Truce of God

And primal meeting of the Sons of Man

Foreshadowing the Union of the World

From all ends of the earth we come. . .

That first afternoon, anthropologist Franz Boas spoke about “The Instability of Human Types.” Race, Boas said, did not determine human intelligence. In fact, separate races no longer existed. Humanity was now richly inter-mingled. “The old idea of the absolute stability of human types must be given up, and with it the belief in the hereditary superiority of certain types.”

Humanists spoke of brotherhood while scientists denounced racial superiority, racial inheritance, racial nonsense. “If is of no more importance to know how many races there are than to know how many angels dance on the head of a needle.”

The better part of each day was spent listening to papers. “The Respect Which the White Race Owes the Other Races,” “The Present Position of Woman,” “The North American Indian,” “Meaning of Race, Tribe, Nation.” Acoustics in the old hall were bad, and much was lost in translation. Yet as delegates teemed through the halls, they soared on a shared sense of equality, of brotherhood. Many, fearful to even mention race back home, now openly discussed the fate of Negroes, Indians, Afghans, Kurds, plus “special problems” in Turkey, Persia, Egypt. . .

Early in the conference, all delegates filled out a questionnaire.

1) “To what extent is it legitimate to argue from differences in physical characteristics to differences in mental characteristics?”

2) “Do you consider that the physical and mental characteristics observable in a particular race are A) permanent; B) modifiable only through ages of environmental pressure or 3) changeable “within a generation?“

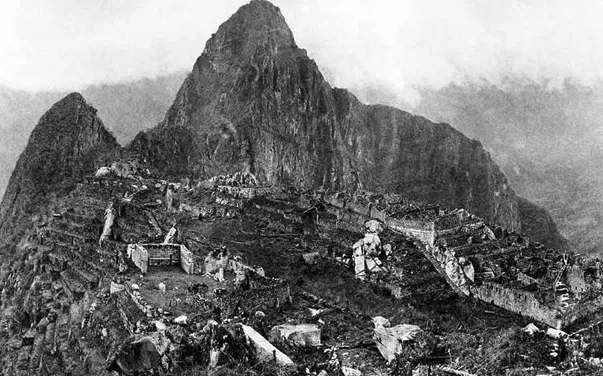

Elsewhere, it was a busy summer, with news ranging from the discovery of Machu Picchu to heat waves killing hundreds. The Universal Races Congress made few headlines. The New York Times scoffed: “There can be no universal ‘melting pot.’” But Science called the conference “a new departure in the history of the world.” And America’s black press called it “the greatest event of the 20th century.”

Later that summer, W.E.B. DuBois would sum up the mood. “Color suddenly seemed a small and unimportant distinction. When fifty races look each other in the eye, face-to-face, there arises a new conception of humanity and its problems.” To critics who claimed the conference did nothing, DuBois replied that the Congress “accomplished wonders. Every word uttered, every step taken by this Congress is in direct opposition to the dominant philosophy of race hatred.”

After three days bathed in sweat but uplifted by hope, 2,500 delegates scattered into a race-torn world. But before adjourning, the Congress approved nine resolutions. Among them:

— To recommend that different races contact each another, always being courteous and respectful. . .

— To point out the absurdity of believing that one’s own customs, civilization, and physique are superior. . .

— to diminish warfare, respect immigrant cultures, and promote education for all. . .

The Congress resolved to meet again — in Paris in 1915. Plans were made, promises offered, goodbyes said in dozens of languages. But by 1915, Europe was at war. No Universal Races Congress was ever held again, leaving the hymn composed by W.E.B. DuBois to echo into our own times.

Save us, world spirit, from our lesser selves

Grant us that war and hatred cease

Reveal our souls in every race and hue

Help us O Human God in this, thy Truce

To make humanity divine.