Griots — Living History Books

FADAMA VILLAGE, GUINEA, WEST AFRICA, 1994 — Behind the small huts, across the scrubby highlands, the river rolls on. Women draw water from it. Children bathe in it. And one afternoon, an old man sits on its bank. His words flow forth like the river itself.

“My name is Tassey Condé,” he begins. “Younger brother of Laye Mamadi Condé who recently passed away.” And now to tell the tale. . .

When Manden was put in the care of Maghan Konfara, he had the power. He had the wealth. He was popular. He had dalilu. But he had no child. You heard it? Simbon, Sunjata’s father, had no child. He craved a child. . .

The man continues, telling the tale of a child born unable to walk. How the boy Sunjata was humiliated, exiled, left to suffer while his own land fell under tyranny. The teller spins his tale, all from memory, talking and talking for six straight afternoons. The tale, like its hero, is called Sunjata. The story tells of a future “Lion King.” And the storyteller is called a griot.

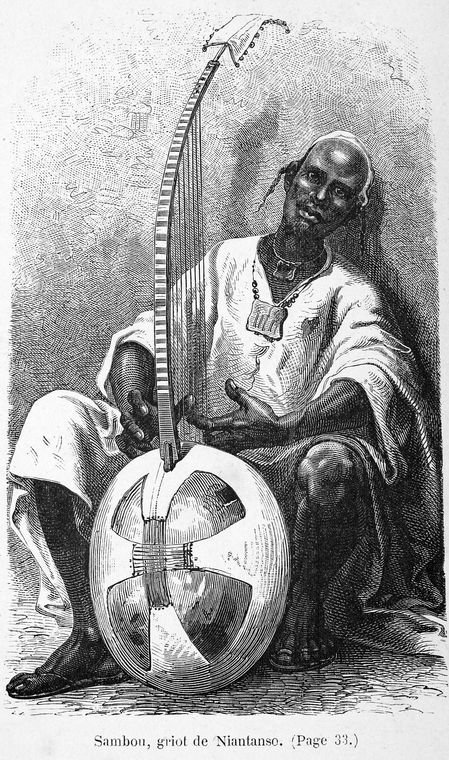

Storytelling is as old as humanity, but throughout West Africa, the griot (gree-oh) is no mere storyteller. A griot, wrote musicologist Francis Bebey of Cameroon, “is a troubadour, the counterpart of the medieval European minstrel.” Others, rejecting any comparison with Europe, are more explicit.

A griot is “the mouth, the ears, the eyes of Mandé people. Whatever the people need to say, it is the griot who says it. Whatever the people need to see, it is the griot who sees it, then describes it, narrates it. That which the king doesn’t want to hear, it is the griot who makes the king hear it.”

In the long history of storytelling, oral tradition preceded print. The Iliad and The Odyssey were memorized and recited for centuries, until finally written down. Likewise much of the Bible. But in West Africa, where print was once as rare as snow, griots retain the power and prestige they have enjoyed since the 1200s. Back in that distant day, Mali was not a land-locked desert but an Empire.

He said, “Mother, I will walk today.” You heard it? . . . Nothing happens before its time. He said, “Go and bring my father’s iron staff.” She went for the iron staff, but he also broke that. He said, “Go and tell my father’s blacksmith. Let him forge an iron staff so I can walk. . .”

A griot is not made but born. The tradition, which often includes playing a kora or other stringed instrument, runs in families. Generation after generation, griots are “living history books.” Keepers of the culture, they often serve kings or other rulers, aggrandizing their feats like modern-day presidential press secretaries. But like Europe’s traveling bards and America’s old folkies, they also speak to the everyday.

At weddings, a griot tells the family histories of bride and groom. In ceremonies preceding births, deaths, hunts and other affairs, the griot is summoned to add the weight of history to the fleeting present. When disputes flare, a griot can mediate, calming roiling waters with the wisdom of the past.

“The duty of the griot in Africa society is very important because they tell the people who they are, where they came from, and where they’re supposed to head to,” said Gambian griot Ahaji Papa Susso (above). “Recounting the tribal history of a people, the griot deals with the reality that happens within the society in the past.” Other storytellers, Suso said, just “deal with mythology.”

Though masters of memory, griots use the oral tradition to localize each story. The tale of Sunjata, for example, spins out in dozens of different versions, depending on tribe, nation, or who is listening.

“Unlike great ancient Greek epics, which have been frozen in time since they were written down,” wrote American anthropologist Hakimah Abdul-Fattah (above), “the Sunjata epic — and other legendary accounts of Sahelian empires — continues to grow and change each time it's told.”

Lest you think an angry planet could use more griots, rest assured that we have them. New Jersey poet Amiri Baraka saw “the word ‘griot’ — the poet, musician, historian, story teller getting known all over the world.” Baraka considered black musicians from Louis Armstrong to Stevie Wonder as American griots. Meanwhile, African-American storytellers, such as Baltimore’s Janice the Griot, are telling tales to children and adults, keeping traditions alive.

And Storycorps, the NPR-backed oral history collective, has its own Storycorps Griot, preserving stories at the Library of Congress and at the Smithsonian’s astonishing Museum of African-American History & Culture.

After six days of telling, Tassey Condé, younger brother of Laye Mamadi Condé, is almost finished. The Fulbright scholar recording his story will soon learn that the griot has only told a fraction of the full tale. But it is enough for now. Guinea is one of the poorest countries, so there is always work to be done. In conclusion. . .

Overcoming his lameness rising to walk, Sunjata soon “grows as strong as a lion.” He gathers an army and returns from exile where he overthrows the tyrant and begins a long and peaceful rule as the original “Lion King.”

They hauled it onto the bank, and Jolofin Mansa himself appeared. He was captured and tied up. They took him to the mansa. Turama’an was the commander at that battle. He brought Jolofin Mansa’s treasure to Ma’an Sunjata. Manden was at last free, and the war was over.

The river flows on.