Strolling with the Flâneur

PARIS, SPRING 1865 — He is alone and thrilled to be so. He has no destination other than the next street corner and he does not know which way he will turn when he gets there. He will walk for hours, wandering, drifting, savoring the sweetness of it all. He has a French name — Jacques or Henri — but also a label that is uniquely French. He is a flâneur.

“The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes,” poet Charles Baudelaire wrote. “His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite.”

Some say that in our hurried times, the aimless wandering of the flâneur is a lost art. Yet walking for the sake of walking, not a hike in the woods but a stroll through an urban wilderness, is making a comeback. Flâneur or its female equivalent, flâneuse — anyone can be one. But first, let’s set out in search of the flâneur.

Flana, in Old Norse, meant “to wander with no purpose.” But it took centuries for the ancient verb to become a pastime and it took Paris to provide the map. By the 1860s, as Impressionists began to capture the crowds and charms of the newly renovated City of Light, many noticed lone walkers among them.

These were not “dandies,” walking less to see than to be seen. Nor were they ordinary tourists on the prowl. As the writer Cornelia Otis Skinner later noted, English has “no Anglo-Saxon counterpart of that essentially Gallic individual, the deliberately aimless pedestrian, unencumbered by any obligation or sense of urgency.” Hence, the flâneur was born.

According to Baudelaire, he (we’ll get to that) “enters into the crowd as though it were an immense reservoir of electrical energy.” And walks. And walks. And soaks up the simplest of human affairs along with the complexities of culture. Behind him, each flâneur leaves a trail of questions.

“Doesn’t he have a job?”

“Is he spying on us?”

“Isn’t he lonely?”

Answers: Yes, no, and on occasion. But as critic Walter Benjamin noted, the art of flanerie is an attitude as much as a hobby. “The crowd was the veil from behind which the familiar city as phantasmagoria beckoned to the flâneur. In it, the city was now landscape, now a room.”

In the 1930s, when photography became portable, strolling camera buffs began taking photos on the fly. Paul Strand, Gary Winogrand, and later Vivian Maier all roamed the streets and brought back snapshots. “The photographer is an armed version of the solitary walker reconnoitering, stalking, cruising the urban inferno,” Susan Sontag wrote. “Adept of the joys of watching, connoisseur of empathy, the flâneur finds the world ‘picturesque.’"

And then it got complicated. Cities became more dangerous, jobs more demanding. Cars made walking passé. And as consumer culture began to consume our spare time, strolling gave way to shopping. By the 1980s, even in Paris, the flâneur seemed like a relic of the 19th century.

The revival came with the word. In the 2000s, flâneur became synonymous with fashion. There is now a Flâneur winery in Oregon and Flâneur Magazine “telling global stories on a micro-local scale from streets all around the world.” Flâneur is a men’s fashion brand selling its name on a T-shirt for $106. Flâneur is a brand of bedding — sheets, pillow, and blanket for $1,600 (not a typo.) But beyond chic, two-legged flâneurs have returned to the streets. Not all of them are men.

Meet the flâneuse.

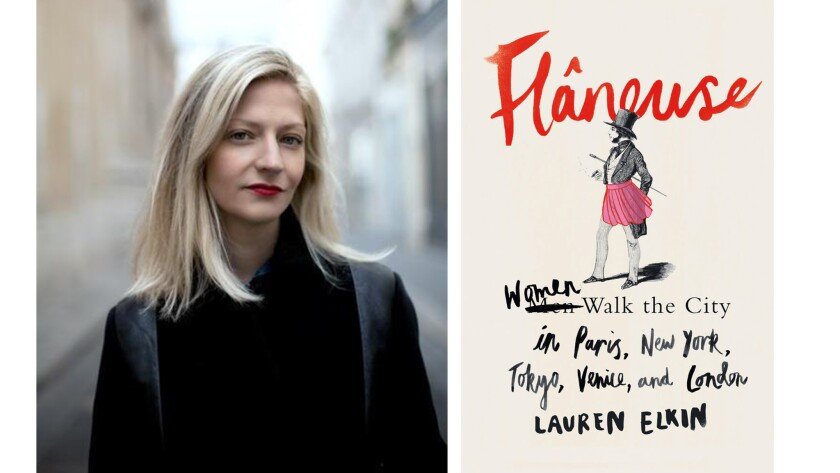

In Wanderlust: A History of Walking, dedicated flâneuse Rebecca Solnit writes: “Walkers are 'practitioners of the city,' for the city is made to be walked.” And in Flâneuse, Laurin Elkin adds: “I walk because, somehow, it’s like reading. You’re privy to these lives and conversations that have nothing to do with yours, but you can eavesdrop on them.”

But here’s the flâneur/flâneuse secret, a secret lost to those confined to cars, bikes, or hiking trails. You don’t have to be in Paris to make walking matter. I have applied the art of flanerie to an afternoon in Hartford, CT, a city I had driven above perhaps 100 times without ever taking an off ramp down to the streets. There I discovered a site where Frederick Douglass spoke, plus old churches, theaters, and the walk Wallace Stevens took to work each day, now noted by plaques excerpting his poetry.

Later, I took flanerie to Manhattan. Setting out at 9 a.m. from 207th street at the northern tip of the island, I spent the day wandering south, always south, through Harlem, Central Park, down Broadway — “Whoa! Empire State Building!” — all the way to The Battery. Manhattan tip-to-tip, 13.7 miles, one day, never forgotten.

So stroll on, flâneur and flâneuse. In defiance of the hurried life, keep roaming, wandering. And at day’s end, advised New York Times travel writer Stephanie Rosenbloom, “What remains of the original privileged character is a certain romance, an air of freedom and a desire to pursue a slower, looser way of experiencing a city — if only for an afternoon. . . You did not go out with a destination. But perhaps you arrived somewhere after all.”